Gut feeling

In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

The important role community pharmacists can play as a source of initial advice and ongoing help in the management of heartburn and indigestion is one that is recognised by NICE and appreciated by customers

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should be able to:

- Explain the causes of heartburn and indigestion

- Advise customers on the most effective way to treat upper GI disorders

- Understand the latest thinking on the GI microbiome.

Upper gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms such as heartburn and indigestion (dyspepsia) are common. Although they can be related to serious underlying conditions such as peptic ulcer and cancer, they are much more often linked to milder conditions and can be relieved by lifestyle measures and OTC medication.

According to NICE Guideline CG184: “Community pharmacists should offer initial and ongoing help for people with symptoms

of dyspepsia. This includes advice about lifestyle changes, using over-the-counter medication, help with prescribed drugs and advice about when to consult a GP”.

This feature will focus on the most common upper GI conditions, and the care and support that community pharmacists and their teams can offer.

Dyspepsia

‘Dyspepsia’ is not a diagnosis but a term used to describe a complex of upper GI symptoms including upper abdominal pain or discomfort, heartburn, acid reflux, and nausea and/or vomiting that have continued for four weeks or longer.

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) distinguishes ‘uninvestigated (or unidentified) dyspepsia’ from diagnosed conditions such as gastro-oesophageal reflux disease (GORD), peptic ulceration or cancers of the oesophagus or stomach. ‘Functional dyspepsia’ is where patients have all the symptoms but no physical abnormality is detected at endoscopy. These distinctions are useful in planning treatment.

Causes of oesophagitis and peptic ulceration

Oesophagitis is commonly caused by repeated reflux of acidic gastric contents into the oesophagus. Unlike the stomach, the oesophageal mucosa has no protection against acid and is damaged by it, leading to inflammation and heartburn. Reflux of gastric contents is normally prevented by the lower oesophageal sphincter (LOSP), which operates like a one-way valve.

Reflux oesophagitis is associated with a weakened LOSP; it is also more common with a hiatus hernia. Oesophagitis can also

be caused by the irritant effects of medication (e.g. iron products; potassium chloride) or by radiation damage (e.g. following X-ray treatment for lung cancer).

Reflux oesophagitis symptoms can include globus sensation (the persistent sensation of a lump in the throat), regurgitation and sometimes wheezing or chronic cough at night due to regurgitated material ‘going down the wrong way’.

In some patients, chronic oesophageal reflux leads to pre-cancerous changes in cells lining the oesophagus, known as Barrett’s oesophagus. About one in 20 patients with Barrett’s oesophagus develops oesophageal cancer.

Peptic ulceration

Gastric parietal cells secrete acid but gastroduodenal lining cells also secrete mucus and bicarbonate that protect the epithelium from the damaging effects of gastric acid (and bile salts, pepsin, drugs, alcohol and Helicobacter pylori infection). Normally, the ‘protective’ and ‘damaging’ effects are held in balance but this can be disrupted, typically by H. pylori infection or NSAIDs.

H. pylori is able to penetrate the dense mucus layer that protects the gastric mucosa. It causes inflammation and worsens ulcers; it also appears to reduce duodenal bicarbonate secretion.

NSAID use is a common cause of peptic ulcer (PU) disease. These drugs disrupt the mucosal permeability barrier, leaving the mucosa vulnerable to injury. Up to 30 per cent of adults taking NSAIDs have GI adverse effects. Risk factors for duodenal ulceration with NSAIDs include history of previous peptic ulcer disease, older age, female sex, high doses or combinations of NSAIDs, long-term NSAID use, concomitant use of anticoagulants, and severe co-morbid illnesses. Physiological stress increases the risk of peptic ulceration.

More than 20 per cent of PU patients have a family history of duodenal ulcers, compared with only 5 to 10 per cent in the control groups.

Did you know?

- Indigestion accounts for up to 4 per cent of all primary care (GP) consultations, with dyspepsia symptoms estimated to occur in about 40 per cent of the population each year

- Indigestion and heartburn can have a significant impact on quality of life

- Reported symptoms are poor predictors of significant disease or underlying pathology

- Initial management of the condition involves lifestyle measures and elimination of drug-induced dyspepsia especially that caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

- Dyspepsia without red flags can be treated empirically with proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) or Helicobacter pylori eradication. Endoscopy is only necessary for patients with red flags or who fail to respond to treatment

- Gastritis and oesophagitis are much more common endoscopic findings than peptic ulceration or cancer

- H. pylori infection and NSAID use account for most cases of peptic ulcer disease

- H. pylori can be eradicated with a seven-day course of treatment using three agents – good adherence is essential.

Treatment

Most patients with dyspepsia prefer self-treatment in the first instance and only seek medical advice if symptoms persist. Pharmacists can support patients to manage, treat and avoid dyspepsia/reflux symptoms. This section provides key points for discussion with patients in line with current NICE guidance:1,2

- Review treatments (prescribed and OTC) to identify drugs that could be causing or exacerbating symptoms. Consider switching or discontinuing any drug that could exacerbate dyspepsia.

In addition to NSAIDs and aspirin, other well-known candidates include bisphosphonates, calcium channel blockers, cortico-steroids, iron preparations and potassium chloride - Advise people to avoid known triggers where possible (e.g. smoking, alcohol, coffee, chocolate, tomatoes, fatty and spicy food

- Raising the head of the bed on blocks (NOT using extra pillows, which simply ‘folds’ the torso and increases back-pressure on the LOSP) and having a main meal three to four hours before going to bed may help to relieve night-time reflux symptoms

- Offer advice on healthy eating, weight reduction and smoking cessation

- Offer guidance on non-prescription medicines for self-treatment of heartburn and/or acid regurgitation, including antacids, histamine-2-receptor antagonists (H2RAs) and proton pump inhibitors (PPIs). Antacids and H2RAs have a rapid onset of action, but the effects of H2RAs last longer. While the onset of action with PPIs is not rapid, the effects last significantly longer.

- PPIs are the agents of choice for persistent, troublesome dyspepsia/reflux symptoms and offer effective, 24-hour acid suppression. Although early pharmacy-only PPIs were low-dose products, full-dose esomeprazole (20mg) and omeprazole (20mg) are now available as GSL items for short-term (up to 14 days) management of reflux symptoms

- The half-life of most PPIs is about one hour, but the duration of acid inhibition is 48 hours

- H2RAs (e.g. ranitidine; famotidine) have a rapid onset of action but less potent effects than PPIs. They are suitable for people with milder, intermittent symptoms

- Antacids have a rapid onset of action but the effects are short-lasting (limited by gastric emptying). They are suitable for immediate symptomatic management and can be most effective when given one hour and three hours after food

- Alginate-containing antacids can be helpful for reflux symptoms. They form a viscous gel when in contact with acid and this sits on the surface of the gastric contents helping to reduce post-prandial acid reflux3

- If possible, provide leaflets and/or signpost people to internet resources for additional support

- Explain that if symptomatic measures do not provide adequate relief, referral for prescribed treatment will be the next step

- Refer when necessary – immediately if red flags are present, and if over-the-counter treatments are ineffective or symptoms worsen.

First-line prescribed treatments for dyspepsia

- For dyspepsia without red flags, NICE recommends empirical treatment with full-dose PPIs or ‘test and treat’ for H. pylori.1,2 Endoscopy is only necessary for patients with red flags or failure to respond to treatment. The prognosis is excellent

- If eradication treatment for H. pylori is indicated, then this will involve a seven-day course of ‘triple therapy’ comprising a PPI twice-daily, amoxicillin 1g twice daily and either clarithromycin 500mg or metronidazole 400mg twice daily. For penicillin-allergic patients the treatment is a PPI, clarithromycin 500mg and metronidazole 400mg all twice-daily. Good adherence is essential.

Most patients with dyspepsia prefer self-treatment in the first instance and only seek medical advice if symptoms persist

Red flags

The following should be viewed as red flags:

Dyspepsia with any of the following:

- Evidence of GI bleeding (vomiting of blood, ‘coffee grounds’ vomit, passage of black tarry stools)

- Progressive unintentional weight loss

- Progressive dysphagia (difficulty swallowing)

- Persistent vomiting

- Epigastric mass.

Patients aged 55 years or more with unexplained and persistent, recent-onset dyspepsia.

The role of GI Bacteria

While we are beginning to understand the human reliance on a healthy gastrointestinal microbiome, much of the detail is yet to be discovered...

Over the past 15 years there has been an explosion of interest in the gut microbiota – the mixture of microbes that live in the human gut, which vastly outnumber human cells and account for about 3 per cent of human body mass.

In many ways the gut microbiota functions like a ‘super-organism’ that processes nutrients, produces vitamins, protects the body from other microbes and shapes the immune system. It is important to note that the microbiome comprises not only bacteria but also archaea, viruses, phages, yeasts and fungi. So far, research has mainly focused on bacteria.

Although the ideal composition of the gut microbiota is not known, there is no doubt that the balance of organisms can be upset by oral antibiotic treatment (known as ‘dysbiosis’). Perhaps the most extreme example of this is antibiotic-associated colitis.

Although research has focused largely on the large intestine microbiota, it is now known that the upper GI tract also has a resident population of microbes. The composition and numbers of organisms in each segment of the GI tract vary according to factors including pH, oxygen levels and the presence of antimicrobial peptides.4 Much of the GI tract is lined by a dense layer of mucus that protects it from microbes’ adverse effects.

The oesophageal microbiome contains predominantly aerobes. GORD is associated with changes in the oesophageal microbiome.

The stomach was long believed to be sterile because of its acidic environment but recent research has shown that it is normally populated by a mixture of species including Prevotella, Streptococcus, Veillonella, Rothia and Haemophilus. The pattern changes when there is infection with H. pylori and this may be partly because H. pylori raises the gastric pH.

While H. pylori can penetrate and infect the dense gastric mucus layer, it is thought to be a harmless, or even beneficial, commensal organism in many people. For example, early colonisation with H. pylori reduces the risk of developing asthma and coeliac disease in later life. Treatment with PPIs and H2RAs also results in alterations to the gastric microbiota, presumed to be due to the long-term suppression of acid secretion.

Small intestine

The microbiota of the small intestine comprises mainly facultative anaerobes and is less diverse than the colonic microbiota. Less is known about this population than the large bowel microbiota because of the technical difficulties of collecting samples – not least rapid transit and the fluctuating environment. But there is growing evidence to suggest that microbiota plays an important role in digestion and nutrient absorption.

One of its core functions is fermentation of simple carbo-hydrates to feed the microbes themselves and also to produce short chain fatty acids that are an important fuel for intestinal epithelial cells. The small intestine the microbiota can respond quickly to dietary changes; for example, a high-fat diet induces expansion of microbes that promote the digestion and absorption of high-fat foods through several mechanisms, leading to over-nutrition and obesity.

References

- NICE. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease and dyspepsia in adults: investigation and management. NICE Clinical Guideline [CG184]

- NICE CKS Dyspepsia – unidentified cause

- Alginate therapy is effective treatment for GERD symptoms: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Leiman DA et al. Dis Esophagus. 2017; 30:1-9

- Gorkiewicz G & Moschen A. Gut microbiome: a new player in gastrointestinal disease. Virchows Arch. 2018; 472:159-172

Opportunity knocks for OTC omeprazole

The OTC launch of Pyrocalm Control Omeprazole 20mg Gastro-Resistant Tablets offers an opportunity for pharmacists to both promote self-care and reduce prescribing

Most people have indigestion at some point and NICE guidelines advise that “...usually, it’s not a sign of anything more serious and can be treated at home without the need for medical advice, as it’s often mild and infrequent and specialist treatment isn’t required”.

NICE goes on to recommend that...”a prescription for treatment of indigestion and heartburn should not be routinely offered in primary care as the condition is appropriate for self-care”.

The NHS spends around £800m a year on medicines prescribed for heartburn and indigestion, with omeprazole accounting for about £40m of this. With Pyrocalm Control Omeprazole 20mg tablets now available OTC, exclusively to pharmacy, patients who would ordinarily need to make a GP appointment can now obtain their PPI treatment direct from a pharmacy.

The launch strengthens the opportunity for pharmacists to help manage demand for services, diverting patients away from avoidable GP appointments and relieving pressure on practices, says manufacturer Dexcel Pharma.

Moreover, it potentially represents a step-change in the treatment of heartburn and acid reflux for patients and the NHS alike, the company adds. This adds to the overall value of choosing a trusted PPI, available OTC, to help patients engage effectively in managing their symptoms.

Savings

One of the aims of the NHS Long Term Plan is to reduce the prescribing of low clinical value medicines that are readily available over the counter in order to save over £200m a year.

It is within these aims – improving patient outcomes, supporting the place of community pharmacy as the ‘high street’ healthcare and medicine provider, affordability and making best use of resources – that Pyrocalm Control Omeprazole 20mg tablets can add most value, Dexcel believes.

The newly switched product, recommended where clinically appropriate, supports choice and helps to manage demand for services. It can be a positive factor within the ongoing, wider measures to divert patients away from avoidable GP appointments.

“The availability of effective OTC medicines for self-treatable conditions, nearer to home, at a time and in a place that suits most people, makes ongoing care, support and advice more accessible,” says the company.

Targeting high prescribing practices

The launch of Pyrocalm Control OTC could divert patients away from avoidable GP appointments for a common, treatable condition, freeing up GP time as well as prescribing resources.

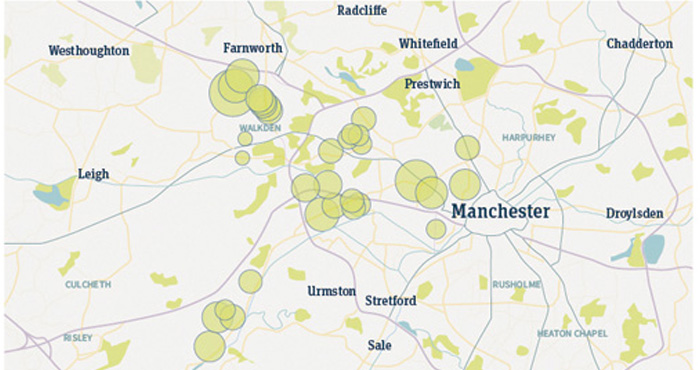

In Greater Manchester alone, 2.3 million prescriptions for omeprazole 20mg were issued between August 2018 and July 2019 at a total cost to local CCGs of around £2.3m, equating to an average spend of £5,050 per GP practice. Savings of nearly £325,000 could be achieved through measures like encouraging patients to self-care, as outlined in the NHS Long Term Plan.

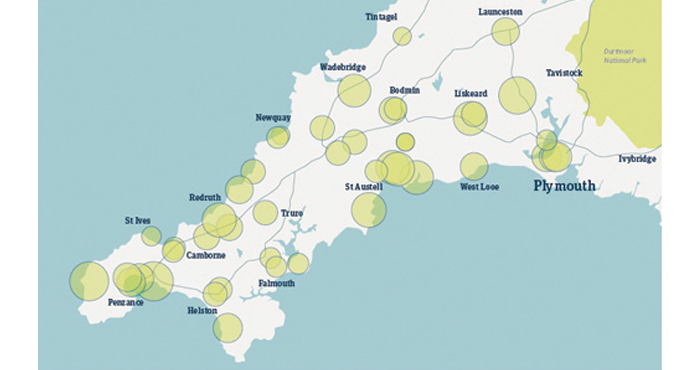

Intelligent use of prescribing data presents an opportunity for community pharmacies to target high prescribing practices. The illustrations (below) map high prescribing GP practices to community pharmacy locations in three geographical areas.

The circles represent pharmacies: the size of the circle is matched to omeprazole 20mg prescribing rates of local GP practices. The larger the circle, the higher the prescribing rate and the bigger the opportunity to target these practices with a view to switching to self-care of heartburn and indigestion symptoms.

- Data provided by health consultancy Conclusio, along with an example of a GP referral form.