Ear problems and their management

In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Our ears have never had to work so hard. The current requirement to wear face coverings in public places can muffle speech and make it difficult to pick up on what is being said – particularly for those who are already hard of hearing

Key facts

• It is estimated that some 2.3 million people experience problems with earwax at a level that requires intervention each year

• In over half of children with acute otitis media, symptoms improve within 24 hours with a full recovery within three days

• Pharmacy teams have a vital role to play in raising awareness of hearing tests and signposting people to these services.

Masks, glasses, earrings, headphones…people’s ears have a lot to contend with and that is before considering how the internal functioning of an organ that is often taken for granted can go wrong.

In this feature we look at some of the common conditions that can affect the ears and the red flag signs that indicate a referral is warranted.

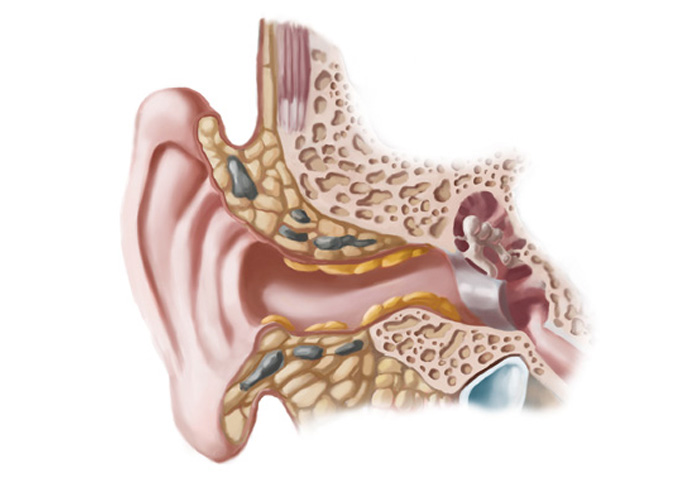

Earwax

Earwax in itself isn’t a problem – it has a number of important functions, including cleaning, lubricating and protecting the lining of the ear canal, but it can become problematic when it builds up or becomes impacted, which can lead to the tympanic membrane (ear drum) becoming obscured or occluded. This can, in turn, impair hearing.

In the UK, some 2.3 million people experience problems with earwax at a level that requires intervention each year, with removal the most common ENT procedure performed in primary care – around 4 million ears are irrigated every year.

Many people with impacted earwax will have identified the problem themselves, usually because of hearing loss, but other signs including feeling that the ears are blocked, uncomfortable or full, itchiness, tinnitus and vertigo. The first indication can be behavioural; hearing loss can lead to frustration, stress, social isolation, paranoia and low mood.

There are several risk factors for earwax, including narrow, deformed or hairy ear canals, drier earwax than normal (which can happen due to ageing), Down’s syndrome and learning disabilities. Use of cotton buds, ear plugs and hearing aids can also increase the risk.

In some cases, the problem resolves spontaneously, but others may benefit from softening treatments or proprietary OTC preparations. There is little to choose between olive oil, almond oil and sodium bicarbonate, all of which have the added bonus of being inexpensive, although ear drops are not advised if a perforated eardrum is suspected. Irrigation may be required but is not suitable for all. Self-cleaning using, for example, cotton buds or ear candles, is not recommended. Someone who suffers from recurrent earwax impaction may benefit from regular use of softening drops.

- A useful resource for patients is British Tinnitus Association: Earwax

- For healthcare professionals, there is the NICE Clinical Knowledge Summary (CKS).

PHOTO CREDIT: SPENCER SUTTON – SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

PHOTO CREDIT: SPENCER SUTTON – SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

Otitis externa

When the external ear canal (the part that extends from the outside of the head to the tympanic membrane) becomes inflamed, it may be localised (as is the case with an infected hair follicle) or diffuse. The latter, also known as swimmer’s ear, may also affect the external ear and the ear drum itself.

Rarely, and predominantly in people who are immunocompromised or elderly, otitis externa can be malignant. This is also known as necrotising otitis, and the aggressive infection spreads into the mastoid and temporal bones surrounding the ear canal. In all its forms, otitis externa is common, with more than 1 per cent of the population diagnosed with it each year. Incidence peaks at age seven to 12 years and towards the end of the summer, but it can affect people of all ages and at any time of year.

The symptoms of otitis externa can include itching and redness of the ear canal or external ear, discharge (otorrhoea), and pain in the ear and on moving the jaw. If the condition has become chronic, the skin may appear dry and thickened, with earwax notable by its absence. Malignant otitis has a very different presentation and can include facial nerve palsy, fever, vertigo, pain and profound hearing loss. An urgent referral is required as it can lead to meningitis.

Localised otitis externa may heal on its own although a pustule may first develop then burst and drain. Self-care measures that can help relieve any associated pain include the application of local heat and use of simple analgesia. Oral antibiotics or incision and drainage are occasionally needed.

Diffuse otitis externa often resolves on its own if it is acute, but there is a place for employing simple analgesia and a topical antibiotic with or without a topical corticosteroid. There is also evidence supporting the use of topical acetic acid spray. Chronic otitis externa is managed using many of the strategies for acute cases, but if it is diffuse it can be more complicated due to the ear canal progressively narrowing and becoming increasingly stenotic, which can lead to deafness.

Acute otitis media

Inflammation of the middle ear causing fluid to accumulate (known as effusion) accompanied by symptoms and signs of an ear infection (e.g. earache, fever, behavioural changes in younger children) is known as acute otitis media (AOM).

Upon examination, the tympanic membrane appears red, yellow or cloudy, and to be bulging or perforated – in the case of the latter, there may be discharge in the ear canal.

AOM can be caused by both bacteria and viruses, and often both are present at the same time. The condition is common in young children, partly because of the frequency with which they acquire viral infections but also because they have shorter and more horizontal eustachian tubes (which connect the middle ear to the rear of the nose). AOM occurs most frequently in the winter.

In over half of children with AOM, symptoms improve within 24 hours with a full recovery within three days. Recurrent episodes are not that common, and where they do exist tend to resolve as the child gets older. Long-term complications are rare, but can include persistent otitis media with effusion (OME), recurrent infections, hearing loss (usually temporary), perforated eardrum, labyrinthitis and – occasionally – spread of the infection to nearby areas causing problems such as mastoiditis, meningitis and intracranial abscess.

The recommended management is simple analgesia. There is no evidence to support the use of decongestants or antihistamines. Anyone who is at high risk of complications or seems very unwell should be offered antibiotics and there is a strong rationale for providing a back-up prescription for some individuals should their symptoms worsen significantly or rapidly at any time or whose symptoms don’t improve. Immediate specialist assessment is advised for those with suspected acute complications, such as symptoms of a severe systemic infection.

If AOM leads to chronic inflammation and recurrent middle ear infection, the condition is known as chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM). The infection may be bacterial or fungal, and while the condition is not that common, it can lead to hearing loss (and problems with language development in children), and the infection may spread intracranially (causing meningitis or cerebral abscess) or extracranially (causing facial paralysis or mastoiditis).

Symptoms that indicate this has happened include headache, vertigo, fever, dizziness, nystagmus and tenderness behind the ear, and warrant urgent medical assessment. CSOM management usually involves topical antibiotics and steroids, plus intensive cleaning of the affected ear. There should be exploration of whether day-to-day functioning has been affected, for example because of hearing loss.

- For patients, the following may be useful: NHS Inform: Middle ear infections

- Good resources for the pharmacy team are NICE: Otitis media and NICE: Otitis media – chronic suppurative

Upon examination, the tympanic membrane in AOM appears red, yellow or cloudy and to be bulging or perforated

Otitis media with effusion (glue ear)

Collection of fluid in the middle ear minus the signs of acute inflammation points to otitis media with effusion (OME), often referred to as glue ear. Over half of cases follow an episode of AOM, with peak incidence in the two to five-year-old age group and in the winter months. Some 80 per cent of children will have at least one episode of OME by the age of 10 years.

OME can lead to significant hearing loss, part- icularly if both ears are affected and the condition lasts longer than a month, and is the most common cause of hearing impairment in childhood. It has also been associated with educational, developmental, behavioural and social difficulties, with speech and language development potentially affected and reports of balance problems, disturbed motor function and clumsiness. Persistent OME can lead to structural damage, sometimes necessitating surgery to the tympanic membrane.

Hearing loss is often the presenting symptom, although it may present as difficulty communicating or listening to music, having the television at excessively high volume, or loss of balance. There may be ear pain, although this is usually mild and intermittent. If there is unpleasant smelling discharge, an urgent referral is needed. Upon examination, the eardrum may appear normal and often there is no sign of inflammation or discharge.

Tympanometry (assessment of the ability of the eardrum to react to sound) and audiometry (assessment of the level of hearing loss, which can be done via visual responses in very young children) may be indicated. Screening is recommended for children with Down’s syndrome or cleft palate who are at increased risk of OME.

Spontaneous resolution is common, although active observation is advised in order to establish whether symptoms are improving or if a referral to an ENT specialist is necessary for hearing loss or developmental delay. Autoinflation (blowing up a balloon via the nostril two to three times a day to ventilate the middle ear, balance pressure and allow fluid to drain) or the Valsalva manoeuvre (achieving the same aims as autoinflation but by forcibly exhaling with the mouth shut and nostrils pinched) may be suitable for older children.

Surgical options include myringotomy (creating a tiny incision in the eardrum) and insertion of grommets (ventilation tubes). A child who has these fitted needs periodic check-ups during which their hearing should be reassessed. Grommets often stop functioning in less than a year and many children need a reinsertion procedure. They are also not without their problems: otorrhoea affects around one in five children, and there is also a risk of infection, tympanosclerosis, eardrum perforation and similar. Parents and carers may be concerned about everyday activities, but can be reassured that school, air travel and swimming are all fine, although diving is not advisable.

A small number of children require hearing aids, namely those who cannot or do not want surgery, but who have persistent bilateral OME. Antibiotics, antihistamines, mucolytics, decongestants and corticosteroids are not advised for the treatment of OME due to a lack of supporting evidence.

- Helpful resources for patients are NHS: Glue ear and GOSH: Grommets

- For the pharmacy team there is: NICE: Otitis media with effusion

Hearing loss

Hearing loss is incredibly common, affecting some 12 million people in the UK. It often happens gradually with others noticing changes, such as the individual turning up the volume on the television or radio, asking people to repeat what they have said or complaining that they are mumbling, or struggling to follow conversations on the phone or in situations where there is more background noise. Sudden onset of hearing loss, in one or both ears, needs attending to quickly as it can be a sign of a medical emergency such as a stroke.

Pharmacy teams have a vital role to play in raising awareness of hearing loss and the benefits of hearing tests, and signposting to such services. While many people develop coping strategies, hearing impairment can have many unforeseen effects, from deterioration of relationships and engagement in social activities, to reduced employment and educational opportunities, independent functioning and quality of life. Health outcomes may also be poorer, with individuals with hearing loss at increased risk of developing depression, anxiety and dementia, and are more likely to experience falls.

Hearing aids are a solution for some – and there are many different types, with technology constantly improving, making them more discrete and offering better sound quality. However, there are also other measures that can help, including cochlear implants and bone conducting hearing implants, and assistive listening devices that amplify sounds from a specific source such as a person speaking, a door bell or TV.

It is also helpful to suggest putting in place adjustments to facilitate good hearing, including reducing competing noises such as background music, improving acoustics by using soft furnishings to reduce echoes, and having adequate lighting and seating arranged to enable people to be seen in order that body language, facial expressions and lips can be read.

Pharmacy teams have a vital role to play in raising awareness of hearing loss and the benefits of hearing tests, and signposting people to such services

- For patients, the charity Action on Hearing Loss has a wealth of information

- For pharmacists and their teams, NICE guidance is relevant

RNID advice during Covid

Government guidance says people do not need to wear a face covering if they have a legitimate reason not to – for example, due to health, age or equality reasons. The Royal National Institute for Deaf People advises people who are deaf or hard of hearing that they don’t have to wear a face covering if:

• They cannot wear their hearing aid or cochlear implant processor securely with a face covering

• Wearing a face covering interferes with their hearing aid or cochlear implant processor

• They are travelling with or providing assistance to someone who relies on lip-reading or facial expressions to communicate.

Plus, anyone can temporarily lower their face covering while maintaining social distancing to communicate with someone who relies on lip-

reading or facial expressions. Retail staff, for example, can lower their face covering to talk to a customer who is deaf or has hearing loss.

“Many of our supporters would prefer people to wear face coverings with clear panels in public settings. This is because they allow deaf people

and those with hearing loss or tinnitus to lip-read,” says the RNID.

“We know they aren’t a perfect solution. Some face coverings with clear panels steam up, which prevents lip-reading and seeing facial expressions. Others may reduce the sound level of some frequencies in speech. This can add an additional challenge during Covid for people with hearing loss.”