In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

We are all unique, thanks to our genome — our genetic make-up, housed within our DNA.

The genome consists of approximately 20,000 genes, and the study of how these genes interact with each other and the environment is known as genomics.

Genes are simply sections of the DNA strand that provide the blueprint for the construction of a vast number of proteins, each serving an important function.

It has been known for decades that within a gene, a sequence of three of the DNA bases – adenine (A), guanine (G), cytosine (C) or thymine (T) – creates a codon that represents a specific amino acid that is incorporated into the final protein.

In recent years, the ability to sequence the whole human genome has revealed how, in many cases, genetic diseases are caused by a change in the DNA sequence of a particular gene or group of genes.

The most common form of genetic change or mutation, responsible for genetic diseases, is known as a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP).

A SNP involves the change of just a single base within a codon. For example, if the normal sequence is ACT, an SNP might change it to AGT.

While a seemingly small change, substitution of a single base can ultimately affect the overall function of the resultant protein and cause a particular disease. Sickle cell disease, for instance, is caused by a single SNP in the beta-globin gene.

Genomic analysis has also unveiled how the presence of SNPs within the genes that encode for drug metabolising enzymes can either increase or reduce the function of these enzymes.

These genetic variants (alleles) have been identified for a range of metabolising enzymes – in particular, the cytochrome P450 isoenzymes involved in the first-pass metabolism of drugs.

The study of how a patient’s genome influences their particular pharmacological response to a drug is known as pharmacogenomics.

“By tailoring drug treatment to match an individual’s genome, pharmacogenomics offers the possibility of an optimal clinical response”

In order to appreciate how and why pharmacogenomics is important, it is necessary to understand the current ‘one size fits all’ prescribing paradigm. For example, imagine a group of patients with high cholesterol who are all given simvastatin to lower their cholesterol.

Taking simvastatin can lead to four different outcomes: the expected clinical response (i.e. lowering of cholesterol), no effect, an adverse effect or a toxic effect.

Although clinicians assume that any given drug will provide the desired therapeutic effect, this assumption is predicated on the notion that inherent individual differences are unimportant.

However, it has become increasingly acknowledged that even when the same drug is given to a group of patients with the same symptoms, the anticipated clinical response is only achieved in between 25 and 60 per cent of them. This variation in response is an implicit recognition of the role of genomic differences.

By tailoring drug treatment to match an individual’s genome, pharmacogenomics offers the possibility of an optimal clinical response to a drug, which is the first step towards the goal of personalised medicine.

In addition, clinicians could identify patients who are more likely to be susceptible to the adverse effects of a drug, allowing replacement with an alternative.

Drug metabolism

The liver is the main organ involved in metabolising around 70 per cent of all drugs. Phase 1 metabolic reactions are largely undertaken by cytochrome P450 (CYP). But CYP450 is not a single enzyme and, to date, more than 57 isoenzymes have been identified, six of which are responsible for 90 per cent of drug metabolism: CYP2C9, CYP1A2, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP2E1 and CYP2A5.

When SNPs arise within the genes that encode for these metabolising enzymes, this can alter the pharmacokinetic effect. On the other hand, SNPs within the genes associated with the action of a particular drug (e.g. receptors) can alter the pharmacodynamic effect.

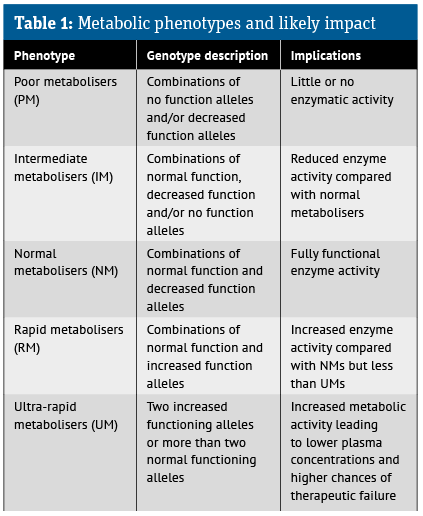

Clearly, the presence of alleles in any of these CYP isoenzymes might affect the functioning of these enzymes and, ultimately, the drug’s therapeutic effect. In addition, based on the impact upon enzyme function, it is possible to identify several different metabolic phenotypes, as shown in Table 1.

Via blood or salvia samples, pharmacogenomic screening prior to treatment initiation can identify an individual’s likely metabolic phenotype, which can then be evaluated in the context of the treatment.

For example, if a patient is prescribed a medicine that is a pro-drug, then for those with a poor metaboliser phenotype, the pro-drug will not undergo sufficient conversion to the active metabolite to provide a therapeutic effect.

Moreover, elevated plasma levels of the pro-drug could give rise to adverse effects. In contrast, patients with an ultra-rapid metaboliser phenotype will require a higher initial dose of a drug to achieve optimal efficacy because the drug is metabolised too quickly and may not reach the required therapeutic concentration in plasma.

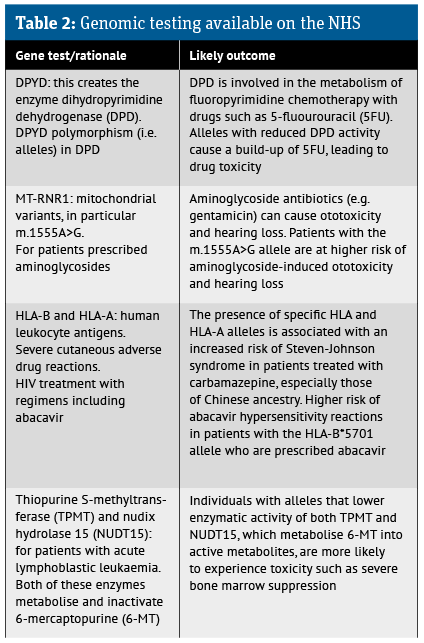

It has also become clear that the presence of certain genetic variants (i.e. alleles) is more common among patients of different ethnicities and this has mandated testing of patients prior to initiation of certain treatments (see Table 2).

Clinical practice

There is a great deal of scope for implementing pharmacogenomic testing in practice. In fact, the NHS Long Term Plan does mention how the power of genomic technology and science will be used to improve the health of the population.

Nevertheless, to date, the NHS only makes use of such testing in a limited number of therapy areas. This limitation is, in part, linked to the possible risk of severe or even life-threatening reactions associated with the treatments in patients with recognised alleles. The current range of NHS genomic testing is outlined in Table 2.

While testing for individual gene alleles that affect the functioning of a single enzyme is of value, a further innovation is the use of simultaneous screening for a range of alleles for different enzymes. This multi-panel gene-drug screening can provide even greater patient benefit.

In a study published in The Lancet, researchers used a panel of 12 genes for which there were known to be problems. More than 7,000 patients were then randomised to either standard treatment or pre-emptive pharmacogenomic testing and their treatments adjusted if necessary.

Overall, 27.7 per cent of patients who were not tested experienced adverse drug reactions, while only 21 per cent of those whose treatment was modified based on the test findings had an adverse effect.

Is pharmacy ready?

To date, a total of 58 gene-drug interaction guidelines have been developed, yet adoption by clinicians has been limited, despite the currently accepted testing described in Table 2.

It seems that the greatest barriers to wider implementation are a lack of understanding of the potential of testing and unfamiliarity with the topic.

A recent review conducted among pharmacists and pharmacy students found that while there were positive perceptions and attitudes towards pharmacogenomics, this was hindered by a lack of knowledge and confidence.

In another survey of community pharmacists, lack of knowledge was also raised as a barrier, with around 60 per cent of the 51 respondents unable to identify drugs that have or could have the potential for pharmacogenomic testing.

Outside of the UK, the situation is different. Pharmacogenomic services are available and have been evaluated in several other countries, including the US, Canada and the Netherlands.

For example, the anti-platelet drug clopidogrel (a pro-drug) is principally metabolised by the enzyme CYP2C19. So, is important to assess a patient’s metabolic phenotype for CYP2C19 prior to commencing the drug since those with a poor metabolic phenotype are unlikely to experience an adequate anti-platelet effect from the drug.

In a US study, researchers examined the value of community pharmacists taking a buccal swab for CYP2C19 testing and analysis.

Based on the results, the pharmacist contacted the prescriber to recommend either continuation of treatment or a change in cases where the testing identified loss-of-function alleles for CYP2C19 and thus a reduced therapeutic effect. While this was only a pilot study, the authors did find that patients and prescribers were receptive to the service.

Similarly, a real-world study using Dutch community pharmacists who were able to order a request for a panel of eight known gene-drug interactions found that nearly a quarter of prescriptions required a change or modification based on the results of testing.

Next steps

Pharmacogenomic testing is a relatively new phenomenon, but evidence suggests there is a willingness among community pharmacists to undertake such a role.

In fact, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society has already provided a position statement in which it states: “Pharmacists are medicines experts with a background of scientific training and are therefore well-equipped to play an integral part in the development of pharmacogenomic testing.”

With sufficient resources and additional training, it is perhaps only a matter of time before community pharmacists begin to play an increasingly important role in the provision of pharmacogenomic testing for patients, with the aim of accelerating down the road towards more personalised medicine and care.

Pharmacogenomics resources

- cpicpgx.org/guidelines: Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) guidelines. These are designed to help clinicians understand how best to use genetic test results to optimise drug therapy

- Pharmgkb.org provides a summary of the CPIC clinical guidelines