In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Learning objectives

After reading this feature you should:

- Understand how different types of wounds compromise the skin

- Know the best course of action for wounds that present in the pharmacy

- Be able to advise on suitable dressings for different types of wounds.

Key facts

- Most wounds heal through a well-defined process but in some cases, this process is arrested and the wound becomes chronic

- Selection of an appropriate wound dressing provides the optimal conditions for wound healing

- Small first and second degree burns can be easily managed with appropriate first aid measures

- Scars represent an over-zealous wound healing process and there are limited effective treatment options.

The skin is the largest organ in the body, accounting for roughly 15 per cent of total body weight. It performs several functions, including temperature regulation and the production of vitamin D. Another important function is the creation of an intact barrier to the outside world, which guards against external hazards.

Wounds and burns damage the skin and ultimately compromise this protective barrier, with an attendant increased risk of infection and dehydration. In contrast, a scar is a sign of an abnormal healing process following damage from a wound or burn. In fact, scars always develop following an injury that extends to the dermis (the middle layer of the skin).

This article provides an overview of wounds, burns and scars, and discusses how each of these injuries can be managed to minimise potential damage to the skin.

1. Wounds

Among healthy individuals, the skin is extremely resilient and has an incredible capacity for repair. Unfortunately, this facility to repair wound damage is less than ideal for a significant proportion of the population.

Data from 2017/18 reveals that the NHS treated 3.8 million patients with wounds. The cost of treating wounds is huge. Again, data from 2017/18 shows that the NHS spent £8.3bn on managing wounds. To put this into context, the cost of wound management was the third highest NHS expense after cancer and diabetes.

Under normal circumstances, wound healing represents a series of well-defined and complex physiological processes that repair and restore damaged skin (an outline of these processes is shown in Figure 1, below).

Wounds are designated as acute or chronic, with the latter category used to define a wound that fails to advance through the different healing stages and persists for longer than four to six weeks.

A wound becomes chronic when there is an arrest in one of the normal stages of healing. Often, the process stalls during the inflammatory phase, and there are a range of factors that can lead to a wound becoming chronic. Some of the more common reasons include:

- Poor circulation (e.g. due to peripheral artery disease)

- Venous insufficiency

- Diabetes

- Weakened immune function

- Nutritional status.

Chronic wounds are estimated to affect around 2.2 million people annually in the UK. Despite the availability of various wound care treatments, however, a large number of patients are unable to access appropriate therapy, which leads to long-term suffering, a reduced quality of life and, ultimately, a greater burden on the NHS.

In some cases, such as leg or foot ulcers, wounds are considered to be non-healing.

Management of wounds

Most acute wounds, such as cuts, grazes, tears, even bites and stings, will invariably heal without any lasting damage, as long as the necessary first aid measures are adopted as soon as possible following the occurrence of the wound. Once a wound becomes chronic, its ongoing management requires specialist assessment.

While the details of such assessments are beyond the scope of this article, a commonly adopted framework for wound assessment is referred to by the acronym TIME. This stands for: Tissue, Inflammation/infection, Moisture imbalance, Edge of wound. The way in which each of these wound attributes influences the healing process are briefly described below:

- Tissue: the type of tissue present in the wound is an important predictor of healing. For instance, if the tissue is non-viable, wound healing is delayed. Non-viable tissue is often referred to as necrosis, eschar or slough. The presence of this non-viable tissue can prolong the inflammatory response and prevent contraction of the wound margin, impeding re-epithelialisation

- Infection/inflammation: wounds are often colonised by bacteria, but any decision to treat an infection should not be based solely on the presence of micro-organisms. Nevertheless, clinically significant infections can lead to inflammation and hinder wound healing

- Moisture imbalance: for a wound to heal properly, the moisture content needs to be finely balanced. When perfectly balanced, this ensures adequate wound healing and supports normal cell proliferation together with the removal of unnecessary tissue via autolysis. Disruption of this fine moisture balance hampers adequate healing. For instance, too much moisture causes maceration at the wound margin, while desiccation slows epithelial cell migration and hinders the activity of the cells involved in the healing process, impairing wound closure

- Edge: a properly healing wound has pink-coloured edges. If raised, red or dusky in colour, this tends to suggest that healing will be impaired, prompting a re-evaluation of the three earlier phases.

Patients will often experience pain when their wound fails to heal properly. However, it is also important to distinguish the pain of poor healing from discomfort arising from the injury that led to the wound (e.g. surgery; trauma).

Wound dressings

An enormous range of wound dressing products are available, and this can lead to confusion for both pharmacists and patients.

Several factors will influence the choice of dressing, including the nature of the wound, treatment goals (e.g. management of infection; exudate), the location of the wound, and patient-related factors such as the capacity to self-care, skin fragility and levels of pain.

It is worth noting that the dressing itself does not strictly heal the wound. Rather, it creates an ideal environment for optimal healing. Furthermore, the type of dressing may need to be changed as a wound progresses through the healing stages.

An overview of some of the different wound management dressings that are available and the type of wounds for which each is most appropriate is summarised in Table 1.

2. Burns

Damage to the skin from a burn occurs following contact with a heat source. The most common types of burn are caused by thermal injury, although a small proportion are due to electricity or chemicals. The term ‘scald’ is commonly used to indicate a burn that arises from contact with hot liquid or steam.

According to the World Health Organization, there are an estimated 180,000 deaths every year due to burns – most of which occur in the home or workplace.

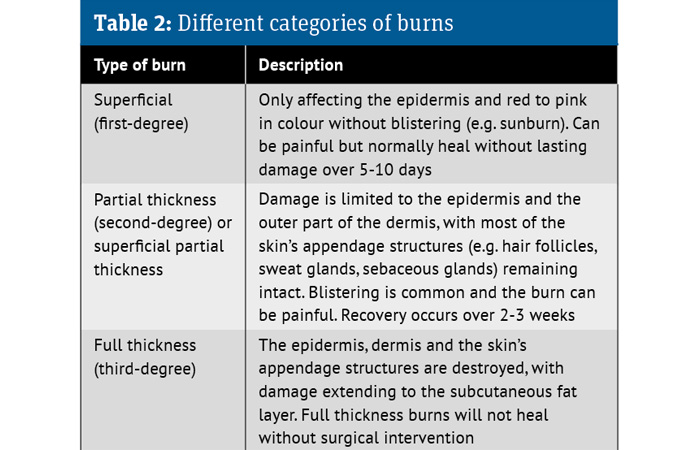

There are several types of burn, categorised based on the extent of anatomical tissue damage they cause. These are described in Table 2.

Management of burns

First degree and small, superficial partial thickness burns can be managed by pharmacy teams. However, any burn or scald that exceeds 10cm in size or has severe blistering or skin discolouration should be referred.

For smaller thermal burns, appropriate first aid measures include:

- Removal of non-adherent clothing and potentially restricting jewellery

- Irrigation of the injury within 20 minutes with cool or tepid running water for 15-30 minutes to stop the burning and reduce the inflammatory process. (N.B. ice or very cold water should be avoided as they can induce vasoconstriction, which may deepen the wound)

- Wet towels or compresses can be used in the absence of running water

- Intact blisters should not be burst, but the burn area can be cleaned gently with saline or water to remove any debris

- If patients are going to hospital, the burn should be covered with cling film. If cling film is not available, a clean, cotton sheet can be used as an alternative.

Pharmacists should also check for signs of active infection (e.g. redness, increased pain or if the patient reports feeling unwell) and advise that the individual maintains adequate hydration.

Any associated pain can be managed with simple analgesics such as paracetamol or ibuprofen. Due to limited evidence, the use of antimicrobial- impregnated dressings or topical agents containing silver sulfadiazine is not recommended for burn management.

Scar management

Watching brief: Kelo-Cote

Kelo-Cote is a silicone gel that has been clinically proven to reduce the appearance of raised scars in more than 80 per cent of people who try it, says Alliance Pharmaceuticals. It has been shown to flatten, soften and smooth scars, relieve itching and discomfort, and reduce discolouration associated with scars. The clear gel is suitable for sensitive skin. It works discretely, under make-up and sunscreen if required, and dries within five minutes of application, says Alliance. The company adds that results are visible in 60-90 days with twice daily application. uk.kelocote.com

3. Scars

The development of a scar following the repair of damaged skin can result in unpleasant physical, cosmetic and psychological consequences. In essence, a scar represents ‘over-healing’ by the skin due to increased production of collagen.

There are several types of scars, including atrophic, which look sunken or pitted; contracture scars, which can limit mobility; and striae or stretch marks. However, by far the most common types of scar are hypertrophic and keloid scars.

Hypertrophic scars develop within the boundary of damaged skin and form within the first month following injury. Little is known about the underlying cause of hypertrophic scars, although both genetic and environmental factors have been implicated. Fortunately, hypertrophic scars often significantly improve over a period of one to two years. On the other hand, keloid scars develop and extend beyond the original wound margin and continue to grow over time. Keloids can arise from any type of injury to the skin, including scratches, insect bites and body piercings.

Hypertrophic scars develop within the boundary of damaged skin

Management of scars

In a review published in Frontiers in Medicine in 2022, researchers evaluated the evidence for topical therapies in scar management, many of which were available for purchase.

There appeared to be some evidence to support the use of aloe vera (which has anti-itch properties), green tea and onion extract (both of which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects.) However, the authors concluded that better understanding of the pathogenic mechanisms of skin fibrosis is required “before we reach the currently unobtainable goal of scar-free healing”.

They also noted that more than a quarter of people with scars in the UK suffer short-term psychological or physical problems as a result.

The role of pharmacy teams

Although not well established in the UK, a recent scoping review identified how pharmacists in several other countries are now involved in the provision of services to support wound care.

The scope of involvement ranged from wound assessment and management to supply of wound care products and onward referral to appropriate health professionals. However, the studies failed to clarify the extent of pharmacist involvement in wound care.

Nevertheless, with the provision of suitable training and practice-based guidelines, future work could potentially explore the most suitable ways in which community pharmacists can be incorporated into the wider multidisciplinary wound management team.