In Clinical

Follow this topic

Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

In The Origin of Species, Charles Darwin called eyes “organs of extreme perfection and complication”. He noted, for example, that the eyes were “inimitable contrivances” for admitting different amounts of light.

Indeed, our eyes can readily adapt to a sunny day, which is a million times brighter than a bedroom at night. However, according to the Royal National Institute of Blind People (RNIB), about 2 million people in the UK live with sight loss.

More than half are blind or partially sighted because of long-term, irreversible ocular conditions such as age‑related macular degeneration (AMD), glaucoma and diabetic eye disease.

By 2050, the RNIB suggests that the number of people with sight loss in the UK will probably exceed 4 million. An initiative led by the College of Optometrists estimated that during the next 10 years, the number of people in the UK with late-stage AMD will increase by 24.4 per cent, while there will be 15.9 per cent more people with primary open-angle glaucoma and 16.7 per cent more with vision-impairing cataracts.

Given the inevitable rise in cases, pharmacies could help to alleviate the pressure on GP and hospital services imposed by acute eye conditions.

“Pharmacists are at the heart of community healthcare, often bridging the gap between patients and the medical profession,” says Louise Gow, head of optometry, low vision and eye health at the RNIB. “For patients with additional needs, the role of the staff in a pharmacy can be even more vital.”

The many faces of conjunctivitis

Pharmacists are well-placed to treat acute eye conditions such as conjunctivitis, the most common ocular condition presenting in primary care.

Seasonal allergens like tree and grass pollen, and perennial allergens such as house dust mites, mould spores and animal dander can cause allergic conjunctivitis. Most people who suffer from allergic conjunctivitis experience itchiness in the eyes.

Other symptoms include watery or mucoid discharge, redness and oedema of the conjunctiva, and swollen eyelids. Pharmacists can offer treatments such as antihistamines and self-help advice about protecting the eyes from allergens and using cold compresses to help alleviate symptoms.

A red, gritty-feeling eye usually indicates infective conjunctivitis, which may be either viral or bacterial in origin. Gow says that pharmacists should check for the following symptoms as well as how rapidly they are progressing:

- Type of discharge (watery or sticky)

- Pain severity

- Light sensitivity

- Whether the patient wears contact lenses

- Recent history of possible foreign body.

Most cases of infective conjunctivitis resolve within one to two weeks, but chloramphenicol can help if the cause is bacterial. Pharmacists should discuss simple self-care steps, such as washing hands, pillowcases, towels and flannels thoroughly to hinder the spread of the condition.

The NHS suggests boiling water, letting it cool and then gently wiping eyelashes with a clean cotton wool pad to remove any crusts that have formed around the eyes. Gow says patients can self-manage viral conjunctivitis by using a cold compress on closed eyelids and using artificial tears or lubricating ointments.

Certain patients should be referred to an eye care professional, so pharmacy teams should know the local signposting for urgent eye care.

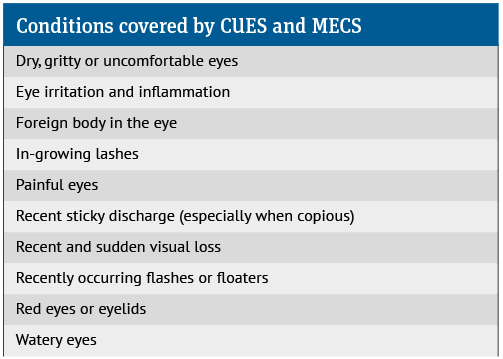

In many areas of England, patients can self-refer to the Community Urgent Eyecare Service (CUES) or the Minor Eye Conditions Service (MECS). Both are NHS-funded.

CUES services are delivered by optometrists who will manage the treatment themselves or make referrals as needed. Based on symptoms, the MECS optometrist service will arrange a phone, video or in-person consultation, typically within 24 hours or a few working days. For mild cases, MECS may advise patients to consult a pharmacist instead.

Pharmacists should refer certain patients to their GP. This includes children younger than two years, people with prolonged or severe conjunctivitis, and those who show a poor response to treatment.

Contact lens wearers with conjunctivitis should be referred to their optometrist as they are at higher risk of more serious sight-threatening infections. Contact lens wearers with infective conjunctivitis should dispose of contact lenses and cases, and not wear their lenses until an eye care professional advises them they can do so.

Dry eye

The Roman writer Aulus Cornelius Celsus noted that dry eyes “neither swell nor run, but are nonetheless red and heavy and painful, and at night the lids get stuck together”. Some 2,000 years on, this description remains evocative, and dry eye is still common.

The term dry eye covers numerous ocular symptoms and signs arising from reduced tear quality or quantity. Many factors cause or exacerbate dry eye, including age, ocular surgery, computer use, contact lenses, low humidity, wind, bright light and temperature extremes.

Several medications, such as antihistamines, ibuprofen, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and eye drops used to lower intraocular pressure in glaucoma, can also cause dry eye.

There are, broadly speaking, two types of dry eye: evaporative and aqueous-deficient.

Evaporative dry eye emerges when tears evaporate too quickly. Common causes include blepharitis (eyelid inflammation) and dysfunction of the meibomian glands. These sebaceous glands produce meibum, an oily secretion that stabilises the tear film and protects against invaders such as microbes.

Aqueous-deficient dry eye develops when the lacrimal gland does not produce sufficient tears.

People with dry eye often experience sore eyes, light sensitivity, a feeling that there is a foreign body or debris in the eye, dryness and irritation.

An evenly distributed tear film is needed to refract and focus light accurately. Dry eye can cause temporary fluctuating or blurry vision and other changes in visual acuity.

Anyone reporting significant pain or a sudden increase in pain or light sensitivity should be referred to the local urgent eye care service. Sudden changes are atypical in dry eye.

Dry eye is chronic, but management, which includes ocular lubricants and warm compresses, can help to control symptoms. Gow notes, for example, that regularly using warm compresses or eye bags can help and sometimes resolve dry eye caused by meibomian gland dysfunction.

“Some people develop sensitivity to the preservative used in eye drops, especially if used frequently, which can make their eyes sore,” she adds. “Preservative-free options can be helpful in these situations.”

Pharmacists should refer people who experience inadequate responses despite using ocular lubricants and warm compresses regularly for more than a month to an optometrist.

Dry eye can also produce watery eyes by triggering reactive tear production. Epiphora refers to a marked overflow, where tears run down the face, usually because of an obstruction in the lacrimal outflow caused by, for example, sinusitis, trauma, inflammation or cancer.

Several common issues, apart from dry eye, can cause reflex tear production. These include conjunctivitis, keratitis, uveitis and foreign bodies. If in any doubt, refer the patient to a GP, optometrist or triage service.

Compliance support

Pharmacists should check that patients are able to administer their eye drops. “For some conditions, such as glaucoma and dry eye, eye drops are a crucial part of management,” says Gow.

“Some patients can find the drops difficult to administer and may feel discouraged from following the treatment. Check with the patient as to how they are getting on with their eye drops. In many cases, an eye drop application aid can enable patients to put drops in independently,” she adds.

Glaucoma UK offers more information about aids for dispensing eye drops.

Walk through your practice

“The environment can be a real barrier for some patients with low vision,” Louise Gow says.

“It is always a good idea to do a walk-through in your pharmacy. Think about how you would experience the service in your practice if you had a sight condition.

“For example, is the signage clear and simple, and have you considered including tactile information for those who can’t read that information? With many products at low level, it is important to help patients navigate to the right place. Consider whether the layout is easy to understand, using simple language that people understand, rather than overly complex medical jargon.”

Gow suggests making sure there are clear pathways within the pharmacy using bright colour-contrasted lines on the floor, and that doorways and pharmacy counters are accessible, with signage placed at eye level.

“Is there a clear demarcation between the doorway entrance and shelves and pharmacy counter?” Gow adds.

Patients need to be able to read the packaging on their medication. “If that information is obscured or in any way inaccessible, there is a real risk of the correct dosage not being followed or the medication being taken at the wrong intervals,” says Gow.

“No one would want to take a gamble by taking a tablet from a packet with no information, whatever their level of vision. ”

Pharmacy teams should always avoid sticking labels over Braille instructions on medicine bottles and boxes. “Although Braille is only used by a small number of people living with sight loss, it is extremely important for those who rely on it. Braille can also enable a parent with sight loss to safely and independently give medicine to their children,” Gow says.

“If you have an app or online system for repeat prescriptions, check that it meets accessibility guidelines and is compatible with any assistive technologies that blind or partially sighted people use,” Gow suggests.

Think about dispensing

“Think about your dispensing processes,” she continues. “Ask patients whether they have any additional needs so those who are visually impaired can be flagged on the [PMR] system.

If the brand of medication is changed for a blind or partially sighted patient, make sure you let them know as they may be relying on the colour or shape of the box, and size and shape of the tablets, to know which ones to take.

“Accessible information, including large print, Braille and audio, gives patients with sight loss more independence and also protects their privacy by ensuring they don’t have to share sensitive medical information with friends or family.

Get into the habit of asking patients about their preferred format,and make sure that it is clearly flagged for all staff, so that all correspondence and information is accessible and patients experience equitable care,” Gow adds.

Pharmacists can help to create environments and practices that support people with impaired vision. With the expected increase in ocular disease, the time is right for pharmacists to take a closer look at eye care.

Medication reviews

Medications applied to the eye can reach the body in sufficient concentrations to cause systemic side-effects. Glaucoma drugs, for example, are applied to the eye at high concentrations.

Drugs applied to the eye drain through the lacrimal duct into the nasal cavity. They are then absorbed through the nasal mucosa.

Conversely, systemic drugs can cause ocular adverse effects. Many are therapeutic mainstays, which pharmacists should consider during medication reviews. For example:

- Sildenafil can cause numerous ocular adverse events – most commonly, colour distortions, blurred and/or disturbed vision. Sildenafil is contraindicated in patients with vision loss in one eye because of non-arteritic anterior ischaemic optic neuropathy

- Between one in 10 and one in 100 people taking duloxetine experience blurred vision. Between one in 1,000 and one in 10,000 develop glaucoma

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors can cause impaired vision, photophobia, conjunctivitis and retinal haemorrhage

- Aminoglycosides may lead to retinal haemorrhages and fluoroquinolones may lead

to retinal detachment.

These examples just scratch the surface. So it is important that community pharmacists and their teams always bear in mind the possible ocular side-effects of systemic treatments.

Eye care resources

- The Royal College of Ophthalmologists: rcophth.ac.uk

- Community Urgent Eyecare Service: primaryeyecare.co.uk/services/community-urgent-eyecare-service

- Minor Eye Conditions Service: primaryeyecare.co.uk/services/minor-eye-conditions-service

- RNIB: rnib.org.uk

- Glaucoma UK: glaucoma.uk