Clinical

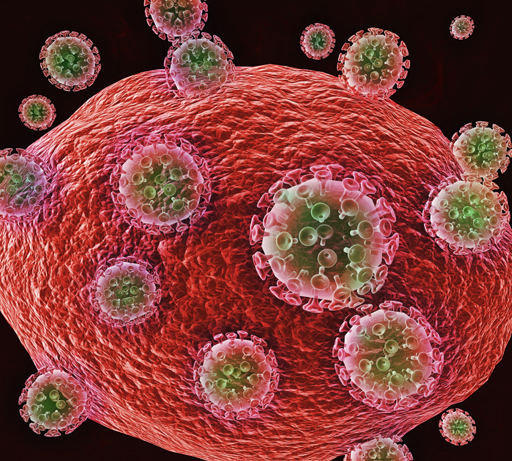

Complex conditions: Treatments for HIV and AIDS

In Clinical

Let’s get clinical. Follow the links below to find out more about the latest clinical insight in community pharmacy.Bookmark

Record learning outcomes

Patients with HIV will be receiving the majority of their care in hospital, but there is still a role for community pharmacists and their teams in providing support and advice.

The human immuno-deficiency virus (HIV) infects and destroys cells of the immune system, notably CD4 cells (which are a class of T-lymphocytes). This renders the body less able to fight infections and disease.

In the UK, most HIV cases are contracted during unprotected vaginal or anal intercourse although, because the virus is found in the cell-containing bodily fluids of an infected individual, it is also possible to acquire it by sharing injecting equipment or sex toys, and through oral sex.

HIV can also be transmitted from mother to baby during pregnancy, childbirth or breastfeeding, but not by social interactions such as shaking hands or sharing items such as crockery and lavatory seats. There is no evidence that HIV can be spread by insects such as mosquitoes.

In the first few weeks after infection, the individual is likely to suffer flu-like symptoms known as primary HIV infection or seroconversion. Because viral load is high, the person is highly infectious to others. Once these symptoms subside, the patient enters an asymptomatic stage, which can range in duration from a year or two to more than a decade

Gradually, the sufferer’s CD4 count drops, and at the point at which it is less than 200 cells per µL, the condition is classed as advanced HIV or Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS). It is at this stage that opportunistic infections such as pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia (formerly known as PCP) and Kaposi’s sarcoma – sometimes referred to as AIDS- defining illnesses, can develop.

According to the Terrence Higgins Trust, in 2015 – the most recent year for which there are complete figures – just over 100,000 people were living with HIV in the UK, of whom some 13 per cent were undiagnosed. Early diagnosis makes a huge difference as delayed diagnosis, and hence starting treatment later than recommended, can reduce life expectancy by up to 15 years.

Treatment options

There is currently no cure for HIV infection but antiretrovirals (ARVs) slow or even halt disease progression. This increases life expectancy and cuts the risk of complications associated with the premature ageing that characterises the condition, although both mortality and morbidity are higher than in individuals who are not HIV-positive. However, treatment is not easy: ARVs have many side-effects, and patients need to be committed and adherent to their regimen.

ARV drugs are used in combinations of three or more. This reduces the chance of the virus, which mutates as it replicates, becoming resistant to the regimen. There are several classes:

• Nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) interfere with the action of an HIV enzyme, halting virus replication. Examples include tenofovir, zidovudine, abacavir and emtricitabine.

• Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) also exert their effect on an enzyme responsible for virus replication, but at a different site e.g. efavirenz, etravirine and nevirapine.

• Protease inhibitors (PIs) block the activity of an enzyme used by HIV to break up large proteins into the smaller pieces required for new viral particles to be assembled. The class includes darunavir and atazanivir. A low dose of one of the PIs, ritonavir, is sometimes used to boost the blood levels of other PIs, meaning doses can be spaced out more than would otherwise be the case.

• Integrase inhibitors (IIs) prevent yet another enzyme assisting viral replication. Examples include dolutegravir, elvitegravir and raltegravir.

• Entry inhibitors (EIs) stop HIV entering host cells, which interferes with viral replication. There are two types: fusion inhibitors, of which enfuvirtide is an example, and co-receptor inhibitors such as maraviroc.

A 28-day course of ARVs may be given as an emergency measure to try and prevent HIV infection. This is known as post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) and is best started within 24 hours of the incident (e.g. unprotected intercourse or a needlestick injury) and certainly within 72 hours.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PreP) also involves taking certain ARVs to reduce the risk of contracting HIV (e.g. for an individual who is going to have sex without condoms with someone who is HIV positive). It can be taken daily, or as a fixed regimen around the time of sex. It is currently not available on the NHS.

Useful advice

Pointers to bear in mind when dealing with patients with HIV include:

• Community pharmacists won’t necessarily know which of their customers have HIV, but patient counselling provides prime opportunities for this information to be disclosed. Encourage this by asking questions concerned with medicines reconciliation, such as whether the patient is being seen at any specialist clinics or takes any medicines that are dispensed elsewhere.

• Offer all patients the opportunity to talk to you in confidence. Some individuals with HIV will want privacy, others like openness, so let them decide where they prefer to have any conversations.

• Be familiar with the names of antiretroviral medicines, the drug classes they belong to and what the tablets look like, as patients may refer to their medication by appearance rather than by brand or generic name. A useful resource is http://i-base.info/guides/category/arvs.

• Don’t make assumptions: patients with HIV are living longer and many have a near to normal life expectancy, so they may well present with the common co-morbidities associated with getting older.

• HIV drugs have a huge number of interactions. Nobody expects a community pharmacist to know each and every one off the top of their head, but it is sensible to know some of the commonest OTC medicines that can cause problems (e.g steroid nasal sprays, multivitamins and indigestion remedies).

• Build up some resources – preferably online as these tend to be kept up-to-date – for checking interactions. A good starting point is the HIV Drug Interaction Checker provided by the University of Liverpool (hiv-druginteractions.org) but don’t be scared to contact your local hospital’s medicines information department and, when they provide an answer, ask where they found it so you can continue to expand your virtual library.

HIV patients are living longer and may have near to normal life expectancy

Â

Get involved

• Reliable sources of information on HIV and AIDS for patients and health professionals include NHS Choices (nhs.uk/conditions/HIV), Terrence Higgins Trust (tht.org.uk/sexual-health/about-HIV) and the National AIDS Trust (nat.org.uk)

• For health professionals, Aidsmap, a website that shares information about HIV and AIDS, is a useful and accessible resource (aidsmap.com/aboutus/who-we-are/page/1276062). Also good is NICE’s Clinical Knowledge Summary on the topic (cks.nice.org.uk/hiv-infection-and-aids), the British National Formulary’s overview of drug treatments (medicinescomplete.com/mc/bnf/current/PHP78275-hiv-infection.htm) and guidelines produced by the British Association for Sexual Health and HIV (bashh.org/guidelines)

• The HIV Pharmacy Association offers support, education and networking opportunities for pharmacists and technicians working with, or who are interested in, HIV and AIDS (hivpa.org). Also of interest may be the British HIV Association (bhiva.org)

• NICE has produced a pathway for HIV testing and prevention, which links to several guidance documents (pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/hiv-testing-and-prevention)

Â

Â